|

| The Institute for Multimedia Literacy, USC (Richard Neutra Building) |

Post written by Elizabeth Cornell. This month Elizabeth Cornell, a doctoral candidate in the Department of English at Fordham University, will be reporting on her summer residency at the NEH-Vectors-CTS Summer Institute at the University of Southern California. She is also the Project Coordinator for the Keywords Collaboratory, a wiki-based space where students and researchers can collaborate on keywords projects inspired by the book, Keywords for American Cultural Studies, edited by Bruce Burgett and Glenn Hendler. This is the first installment of her report. Welcome, Elizabeth!

On a recent plane trip to Los Angeles, I read Jennifer Kahn’s New Yorker profile of Jaron Lanier, a pioneer of virtual reality. According to Lanier, digital technology should aim to enhance and deepen “human interaction”:

“One of [Lanier’s] most recent ventures has been to help Microsoft construct a new, joystick-free gaming system, called the Kinect, which uses a computerized camera to match the movements of a player’s body to the avatar in the game—allowing someone to kick a virtual ninja using her actual foot.”

Lanier considers Kinect, “the fastest selling-electronic device of all time, … an example of technology that could ‘expand what it means to think.’” To me, a real human kicking a computerized ninja is a strange, if not depressing, example of digital technology expanding the mind and deepening human interaction. Maybe I’m not fully appreciating the technological expertise behind a joystick-free video game.

Perhaps my reaction to that comment is because in the digital humanities, real human interaction and collaboration, exciting thinking and knowledge production, is taking place through the use of technology. Some of it is happening at the National Endowment for the Humanities Vectors-CTS Institute at USC. For one month this summer, twenty researchers from various North American institutions are attending the Institute to learn about software platforms designed specifically for use by humanities scholars. The projects this summer are contextualized within the field of American Studies, but the similarities end there. And, no joysticks are in sight.

For example, Curtis Marez, an associate professor in ethnic studies at UC San Diego, is developing a project that uses Cesar Chavez’s video library to explore the role that video and photography and played in struggles between California corporations and workers of color in the agricultural industries of the San Joaquin Valley from the 1940s to the 1990s.

Nicholas Sammond, an associate professor of cinema studies and English at the University of Toronto, is creating a project that examines the relationship between the industrialization of American commercial animation and blackface minstrelsy. Why, he asks, does Mickey Mouse wear white gloves?

Like many people attending the Institute, both Curtis and Nic are using historically significant archives of film and photography to build on the material in their print-based books on related subjects. To create their projects, they’ll use two different but connected software platforms called Hypercities and Scalar. Unlike a book, which is static, these two platforms allow users to add additional visual material to the database, as well as detailed commentary, audio, and interactive maps. Visitors can leave comments; in some cases they can add their own archival material and create new links and paths to related web sites and archives.

If Lanier and, for that matter, his boss, Bill Gates, really want to see digital technology in meaningful action, they should visit USC’s NEH Vectors Institute this summer, where people are using technology to expand the way we think and using it to produce knowledge in innovative, significant ways.

I’ll be at the Institute until mid-August, where I’m exploring ways that Scalar and Hypercities might make Prof. Glenn Hendler’s Keywords Collaboratory a more dynamic, multimodal space for students and researchers. In my next blog entry, I’ll write more about that.

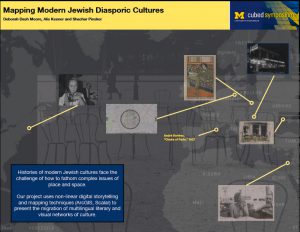

Histories of modern Jewish cultures face the challenge of how to fathom complex issues of place and space. Join Shachar Pinsker (University of Michigan) on April 19th, 2:30pm (Lowenstein 906) to learn about his collaborative digital project, Mapping Modern Jewish Diasporic Cultures, that explores modern Jewish cultures and migrations using non-linear digital storytelling and mapping techniques (ArcGIS & Scalar).

Histories of modern Jewish cultures face the challenge of how to fathom complex issues of place and space. Join Shachar Pinsker (University of Michigan) on April 19th, 2:30pm (Lowenstein 906) to learn about his collaborative digital project, Mapping Modern Jewish Diasporic Cultures, that explores modern Jewish cultures and migrations using non-linear digital storytelling and mapping techniques (ArcGIS & Scalar). Using innovative digital tools and databases, this project aims to visualize the tension between the transnational and diasporic, but also grounded in a particular place; belonging to both global and local cultures. The project scholars, who include Pinsker, as well as Deborah Dash Moore and Alix Keener, hope to take macro and micro views of this network of people, analyzing both the diasporic and individual levels, as well as a multimedia view, such as visual and textual analogs.

Using innovative digital tools and databases, this project aims to visualize the tension between the transnational and diasporic, but also grounded in a particular place; belonging to both global and local cultures. The project scholars, who include Pinsker, as well as Deborah Dash Moore and Alix Keener, hope to take macro and micro views of this network of people, analyzing both the diasporic and individual levels, as well as a multimedia view, such as visual and textual analogs.